- Shop

New to UCAN?

- About

- How to use ?

- Learn

- Contact us

Steady State Cardio: The Practical Guide to Building Endurance

By Generation UCAN. Last updated: October 29, 2025.

Alright, let’s cut through the jargon. Steady state cardio is simply exercising at a consistent, manageable intensity for a decent chunk of time. In practice that means a pace you could hold a conversation at — not an all-out sprint — and not aimless miles. If you’re preparing for the Melbourne Marathon, Gold Coast Marathon or Ironman Cairns, steady state cardio is your non-negotiable base work. In the first 100 words here we use the primary keyword — steady state cardio — and then show you exactly what to do, why it works, and how to plug it into a real Aussie training week.

Contents

- 1 What Steady State Cardio Actually Means for You

- 2 How Steady State Cardio Builds Your Race Day Engine

- 3 How to Find Your Zone 2 Effort (Without Getting It Wrong)

- 4 Simple Steady State Sessions You Can Use — Plug-and-Play

- 5 Your Fueling Strategy For Long Haul Endurance

- 6 Integrating Steady State Cardio Into Your Plan

- 7 Your Questions on Steady State Cardio, Answered

- 8 References

- 9 Call to Action

What Steady State Cardio Actually Means for You

Look, I’ll be straight. The term “steady state cardio” can sound textbook, but for the athlete on a training block it’s the difference between finishing and competing. This is targeted, paced work in Zone 2: long, continuous efforts aimed at increasing aerobic capacity, mitochondrial function and fat oxidation. It isn’t a recovery jog and it isn’t a tempo session — it sits between those two, with a precise training purpose.

- HIIT (flashy, short-term gains): short all-out efforts that raise VO₂max and top-end speed.

- Steady state cardio (the foundation): sustained, sub-threshold work that builds durability, mitochondrial density and metabolic efficiency.

Steady state cardio is the slab your race-specific speed and strength are built on — treat it like the foundation, not filler.

What to do (summary): typical sessions are 45–90 minutes at a conversational pace (talk-test positive) or at a heart rate that matches your aerobic ceiling (see MAF 180 below). Why it works: repeated low-to-moderate intensity stress drives mitochondrial biogenesis and improves fat oxidation capacity. How to apply: slot 2–3 steady state sessions per week during base blocks; include one longer weekend session (see session examples below). :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

The Real Job of Steady State Training

- Build mitochondrial capacity: more and better mitochondria mean greater aerobic ATP production, delaying reliance on anaerobic glycolysis and preserving glycogen. In long races, mitochondrial adaptations equal sustained power. :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

- Improve fat oxidation: steady low-intensity training teaches muscle to use fatty acids as a reliable fuel source, sparing limited carbohydrate stores for surges and finish-line efforts. This shift raises the threshold for metabolic fatigue. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

These changes are both structural (mitochondria, capillary density) and metabolic (enzyme profile, substrate preference). That’s the core adaptation you want from steady state cardio — not immediate speed, but the engine that lets you produce speed for longer later in the season. :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

How Steady State Cardio Builds Your Race Day Engine

Picture two fuel tanks: a small, high-octane carbohydrate tank and a huge diesel tank of body fat. The goal of steady state cardio is to teach you to tap that diesel tank efficiently so you don’t run out of the high-octane fuel when it matters (the final 10–15km of a marathon, the last hour of an Ironman bike, or the closing run leg in a triathlon).

Why This Actually Works: Becoming Metabolically Efficient

What to do: consistent Zone 2 sessions (45–120 minutes depending on discipline and event) performed with strict intensity control (talk test / HR ceiling). Why it works: repeated exposure increases fatty-acid transport and mitochondrial enzymes, raising your maximal fat oxidation rate and extending the time you can tolerate race pace. How to apply: treat the long weekend run/ride as both training and a test for race fuelling and gut tolerance. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

This is the training that separates athletes who finish from athletes who perform — steady work builds a body that can sustain hours of effort without crashing.

The Lactate Clearing Advantage

What to do: sustained low-intensity sessions and occasional tempo blocks that remain below or at lactate steady-state to improve shuttle/recycling mechanisms. Why it works: training at aerobic intensities improves lactate uptake by the heart and slow-twitch muscle fibers, and improves monocarboxylate transporter expression — meaning you produce less fatigue for a given power output. How to apply: you’ll feel better through hard intervals, and recovery between repeats will be quicker — exactly what matters in races with surges or climbs. :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

How to Find Your Zone 2 Effort (Without Getting It Wrong)

Too many athletes treat “easy” as “faster than easy” and sabotage the stimulus. Zone 2 is precise. Below are practical, coach-driven methods to find it.

The Easiest Method: The Talk Test

What to do: during the session, attempt comfortable, full-sentence conversation. If you can speak in sentences without gasping, you’re almost certainly in Zone 2. Why it works: speech correlates with submaximal ventilation and a metabolic state that favours aerobic fuel use. How to apply: use this on easy group runs; if mates drag you to 1–2 word breathless chat — hold them back. This was the foundation I use with athletes prepping for Sydney and Melbourne marathons.

Using Heart Rate: A Simple Formula

Heart-rate methods give an objective ceiling for Zone 2. One practical and widely-used approach is Phil Maffetone’s MAF 180 formula:

- Start with 180.

- Subtract your age.

- Adjust: −10 if recovering from major illness/meds, −5 if injured or frequently sick, +5 if you’re highly trained and improving.

What to do: use the resulting number as your top-end HR for steady sessions. Why it works: it provides a personalised aerobic ceiling that promotes mitochondrial and metabolic adaptations when respected. How to apply: run or ride at or below this heart rate for the session duration, and re-check pace improvements at the same HR over weeks to track progress. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

The goal: finish your session feeling like you could have gone another hour. That’s how you know you’ve hit Zone 2.

Simple Steady State Sessions You Can Use — Plug-and-Play

Below are coach-tested, discipline-specific sessions that meet the “what / why / how” test. Keep intensity strict. If your ego wants faster, let it — but don’t on these days.

For the Marathon Runner

- What to do: 90-minute Zone 2 run (talk-test positive; HR at or below MAF 180 result).

- Why it works: long-enough stimulus for mitochondrial signalling and fat oxidation adaptations without excessive recovery cost. :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

- How to apply: slot as weekend long run in base block. Hills: shorten stride and maintain HR, don’t chase pace up slopes. Trial race fuelling (pre-gel timing, hydration) here.

Fueling tip: a slow-release source 20–40 minutes pre-session prevents reactive sugar spikes — UCAN Energy Gel (LIVSTEADY) is used by many athletes to preserve fat-burning while supplying steady fuel.

For the Triathlete or Cyclist

- What to do: 2-hour Zone 2 ride on flat or slightly rolling terrain; indoor trainer ideal in hot/humid conditions.

- Why it works: extended low-intensity time builds muscular endurance and metabolic efficiency specific to cycling demands.

- How to apply: use cadence and power (or HR) to remain steady; long rides are opportunities to refine on-bike nutrition and hydration.

For the Time-Crunched Athlete

- What to do: 45-minute Zone 2 session (run/ride/row).

- Why it works: preserves aerobic stimulus with low recovery cost; consistent short sessions maintain and slowly improve the base.

- How to apply: place the 45-minute steady day after a hard session for “active recovery plus” — it aids circulation and clears metabolites without adding fatigue.

Embed:

Your Fueling Strategy For Long Haul Endurance

Training to burn fat and then handing your body a sugary gel every 30–45 minutes is contradictory. If your steady sessions aim to increase fat oxidation, your fuelling should support that aim.

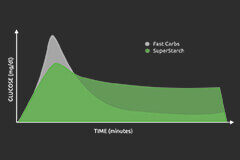

Ditching The Spike And Crash for Steady State Cardio

What to do: prefer slow-release carbs or low-glycemic options before training; avoid high-glycemic gels during base aerobic sessions unless you feel bonking. Why it works: a rapid glucose spike triggers insulin and temporarily halts fatty-acid mobilisation; that reverses the adaptation you’re aiming for. How to apply: for base long runs try a pre-load strategy (UCAN Energy Gel 20–30 min before) and only use mid-session carbohydrate if you have clear signs of energy failure. :contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}

Your Simple Fueling Blueprint

- Before your session: UCAN Energy Gel 20–30 min prior for steady-release energy.

- During (only if needed): small, measured feeds based on time-on-feet and GI tolerance.

- After (within 1 hr): UCAN Energy + Protein to support recovery and glycogen resynthesis without a big insulin spike.

This is practical, not ideological: if your long run is 2+ hours and you’re racing an Ironman-distance event, practice mid-session fuelling; if your session purpose is metabolic adaptation (Zone 2), keep mid-session carbs minimal. Product mentions here are purpose-driven — they are tools, not the point.

Integrating Steady State Cardio Into Your Plan

Building Your Aerobic Base

What to do: adopt an intensity distribution biased toward easy training. Many successful athletes follow a heavy easy / light hard split. Why it works: higher volumes at low intensity conserve recovery and maximise aerobic adaptations; Seiler’s work shows elite profiles commonly spend most time at low intensity. How to apply: aim for roughly an 80/20 distribution of easy vs. hard training during base phases — 80% steady state cardio, 20% targeted high-intensity work. Adjust volume to event distance. :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

Structuring Your Week

- 2–3 steady state sessions: one long weekend session (45–120 min depending on event), one mid-week 45–75 min session, and one short recovery-plus steady ride/run if time permits.

- 1–2 targeted sessions: intervals, threshold or hill repeats — keep these focused and sharp.

- Strength & mobility: two short resistance sessions per week on easy days to improve durability and power transfer.

Go slow to get fast — the thousand steady kilometres are what let you turn up the top-end work without breaking down.

Beyond Cardio

Strength training on easy days protects you on race day: stronger hips, better posture and improved running economy. This concurrent training doesn’t stop mitochondrial adaptation — resistance work can complement endurance adaptations when programmed correctly. :contentReference[oaicite:10]{index=10}

Your Questions on Steady State Cardio, Answered

How often should I be doing steady state cardio each week?

For most endurance athletes, 2–3 dedicated steady state sessions per week is ideal — adjust the total volume by event. Consistency over months builds the aerobic engine. (Steady state cardio remains the primary keyword here.)

Is steady state cardio just a fancy name for a recovery run?

No. Recovery runs target Zone 1 for circulation and repair. Steady state (Zone 2) is a purposeful training stimulus with measurable adaptations — longer, slightly harder and done with strict intensity control.

Can I do steady state cardio on a treadmill or indoor trainer?

Absolutely. Indoor trainers and treadmills let you nail consistent intensity — ideal during hot Aussie summers or humid Brisbane mornings when environmental stress would otherwise push heart rate up and ruin the stimulus.

References

[1] Mølmen KS, et al. Effects of Exercise Training on Mitochondrial and Capillary Content and Distribution in Human Skeletal Muscle. (2024). PubMed.

[2] Yan Z, et al. Exercise training-induced regulation of mitochondrial quality. J Physiol. (2012). PMC.

[3] Chávez-Guevara IA, et al. Toward Exercise Guidelines for Optimizing Fat Oxidation. (2023). PubMed.

[4] Casado A, et al. Does Lactate-Guided Threshold Interval Training within a High-Volume, Low-Intensity Approach Improve Performance? (2023). PMC.

[5] Seiler S. Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes. (2006). PubMed.

Call to Action

If you want to implement these sessions cleanly, start with the pre-session strategy below and test one tweak per week. When you’re ready to trial fuelling options that support Zone 2 adaptations, check the UCAN range — purpose-driven, slow-release energy options used by athletes during base blocks.

👉 UCAN Energy + Protein (Recovery)

👉 Complementary Strength Workouts for Endurance Athletes

Quick Takeaways

- Steady state cardio (Zone 2) = targeted metabolic adaptation, not casual miles.

- Stick to strict intensity (talk test / HR ceiling) and prioritise 2–3 sessions weekly.

- Fuel to support, not to override, the adaptation — consider slow-release options pre-session.

Author: Generation UCAN — trusted coach voice for Australian endurance athletes.

Comments are closed