- Shop

New to UCAN?

- About

- How to use ?

- Learn

- Contact us

The Straight Dope on Healthy Deep Frying Oil for Athletes

Let’s be blunt: the phrase healthy deep frying oil sounds like something out of a wellness meme. You’re 30–35 km into a training run for the Gold Coast Marathon, your legs are heavy and your head’s full of race strategy — the last thing you expect to be thinking about is frying oil. But if you care about inflammation, recovery and real-world race nutrition, the oil you use for the occasional fry matters. This guide gives you the what, why and how — with coaching-level specifics for Aussie endurance athletes.

Quick takeaways: pick oils high in monounsaturates or saturated fat for deep frying; smoke point matters but oxidative stability matters more; reuse only when filtered & stored correctly; avoid standard PUFA-heavy seed oils unless labelled high-oleic.

Contents

- 1 The Honest Truth About Frying & Performance

- 2 Why Smoke Point Isn’t the Whole Story (Not Even Close)

- 3 Understanding Oil Stability: The Real Hero of Healthy Frying

- 4 How to Deep Fry Smarter at Home

- 5 Frying Oil Myths That Drive Me Crazy

- 6 Frying Oil FAQs: Your Questions Answered

- 7 References

- 8 Practical UCAN Notes & Product Mentions (applied to training)

- 9 Author & E-E-A-T

The Honest Truth About Frying & Performance

First up, let’s get one thing straight: deep frying gets a bad rap for good reasons — but the cooking method alone isn’t the full story. Blaming the technique is like blaming your watch for a lousy split; the real issue is inputs. For athletes who race in Sydney, Melbourne or Ironman Cairns, marginal gains matter: a drop in systemic inflammation across a training block can influence recovery, sleep and next-session intensity. That’s where the frying oil comes in.

Here’s how we’ll approach it from a coach’s perspective: for each practical recommendation I’ll cover what to do (actionable), why it works (physiology/chemistry), and how to apply (when in a training microcycle or race week). If it doesn’t pass that test, it’s cut.

Short example — what this looks like in practice: the night before a hard interval session (8×800m @ 5k pace), use a meal cooked in a heat-stable oil (e.g., neutral avocado or ghee-based roast potatoes). Why? Less oxidative load and fewer reactive lipid by-products that can increase post-session inflammation and blunt recovery. How to apply: replace PUFA-heavy takeaway fry oil with a stable oil for race-week or heavy-training-week meals and keep servings moderate (one palm-sized serve of fried carbs, not a whole bucket).

Put simply: deep frying is a tool. Used well, it gives reliable texture with tolerable metabolic cost. Used carelessly, it’s a fast track to increased oxidative stress and poorer recovery.

Your Quick Guide to Choosing a Frying Oil

| Characteristic | Why It Actually Matters for an Athlete | What to Look For |

|---|---|---|

| Smoke Point | When oil smokes it’s degrading and producing polar compounds and volatile aldehydes. Frying is done at ~175–190°C, so a smoke point higher than that gives margin for error. | Aim for smoke points safely above 190°C for deep frying — refined avocado oil, ghee, refined olive oil are good examples (see References for details). [1][2] |

| Oxidative Stability | This is the oil’s resistance to oxidation under heat, oxygen and light — the main driver of harmful lipid oxidation products that promote inflammation. Oxidative stability often trumps smoke point for health-relevant outcomes. [3] | Choose oils higher in monounsaturated and saturated fats — these oxidise slower under frying conditions. |

| Fatty Acid Profile | Saturated and monounsaturated fats are more structurally robust; polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) have multiple double bonds that are reactive and break down into aldehydes and oxidised lipids. These compounds are what we want to minimise across a heavy training block. | Avoid oils high in linoleic acid (standard sunflower, safflower, many cheap ‘vegetable oils’) for high-heat frying unless labelled ‘high-oleic’. |

These three pillars — smoke point, oxidative stability, and fatty acid profile — are your decision matrix in the supermarket aisles.

Context note: Australian shoppers gravitate toward canola and blended vegetable oils (large market share), but popularity ≠ optimal for high-heat frying in performance contexts. For a market overview see national oilseed reports (USDA / industry reviews). [4]

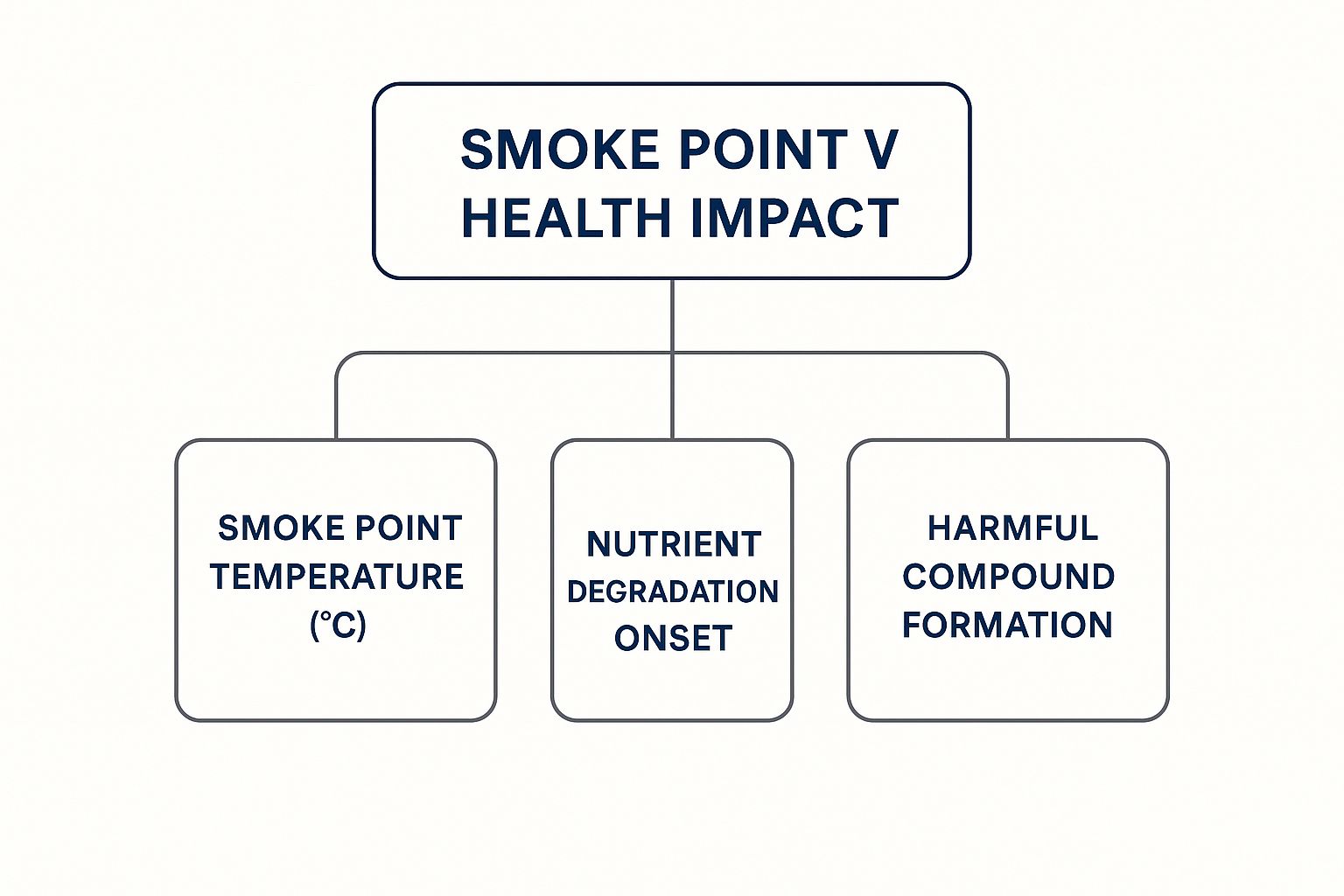

Why Smoke Point Isn’t the Whole Story (Not Even Close)

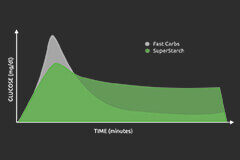

Every quick listicle treats smoke point like the holy grail. It’s visible and simple — which makes it easy to misuse. Consider two oils with the same smoke point; one might be monounsaturated-heavy, the other PUFA-heavy. Under repeated or prolonged heat the PUFA-rich oil will generate many more oxidative breakdown products long before you see smoke. The result: silent damage to meal quality and an avoidable oxidative load for your body. [1][5]

From a performance perspective, that invisible oxidative load matters because inflammation accumulates over days and weeks. If you’re doing back-to-back long runs or a heavy block before Melbourne Marathon, two or three meals a week fried in unstable oil may alter recovery markers and perceived readiness. That’s the measurable cost we care about.

Why Stability Is the Real MVP

Stability = how long an oil resists oxidation under realistic cooking. Research on frying stability — including studies on high-oleic oils — shows these varieties produce fewer polar compounds and aldehydes during long-term frying cycles. In real words: better stability = fewer nasty breakdown products and less inflammatory signalling post-meal. [2][6]

What to do (coaching action): when you plan heavy sessions or race-week meals, prioritise cooking methods and oils that minimise oxidation (roasting in ghee, shallow frying in refined avocado, or air-frying as an alternative). Why it works: fewer reactive lipid products produced. How to apply: in the 7-day lead-up to a key event (e.g., Sydney Marathon), reduce PUFA-heavy fried meals to zero and use stable oils for occasional crispy food.

What Really Happens When You Turn Up the Heat

If you’re using a domestic deep fryer or a heavy pot, aim for a steady range: 175–190°C. Below that, food soaks oil; above that, you char the crust and risk rapid oxidation. The sweet spot is where starch gelatinisation and Maillard reaction produce crispness and flavour without unnecessary thermal breakdown of the oil.

Pro Tip: use a probe thermometer and practice batch control. For small kitchens, 175–180°C is your friend; for professional fryers you can push toward 185–190°C briefly for certain items but monitor closely.

What to do: always preheat oil and confirm temperature between batches. Why it works: consistent oil temperature limits the time oil spends at damaging temperatures and reduces absorption. How to apply: schedule frying in your Sunday meal prep — preheat 10–15 minutes, use a thermometer, don’t overfill the fryer or pan.

Understanding Oil Stability: The Real Hero of Healthy Frying

We go back to the chemistry for a moment because it shapes real-world choices. Stability is a product of the oil’s fatty acid composition and the presence (or absence) of natural antioxidants. Oils with high monounsaturated fat (oleic acid) and saturates stand up to heat better; oils with lots of linoleic acid (an omega-6 PUFA) are a disaster under prolonged or repeated heating. Recent reviews on frying-related lipid oxidation and the toxicological concern of aldehydes give us good mechanistic evidence for prioritising stability. [1][3]

The Fatty Acid Breakdown: What Makes an Oil Tough

- Monounsaturated & Saturated Fats: structurally simpler, fewer double bonds, slower oxidation — examples are avocado, olive (refined), peanut, ghee, tallow.

- Polyunsaturated Fats (PUFAs): multiple double bonds, highly reactive under heat — examples include standard sunflower, safflower, corn, and many cheap blended ‘vegetable oils’.

Coach application — what to do: treat PUFA-heavy frying as an exception, not a habit. Why it works: reduces chronic exposure to oxidised lipids that can raise inflammatory cytokines after multiple exposures. How to apply: limit PUFA frying to rare occasions and avoid reheating the same PUFA oil multiple times.

Two oils with identical smoke points can perform very differently under repeated frying. Pick the oil with the better oxidative stability.

Comparing Popular Frying Oils: The Coach’s Pick

Below is a side-by-side table — practical numbers and suitability ratings you can use in the pantry.

| Cooking Oil | Smoke Point (°C) | Primary Fatty Acid | Deep Frying Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avocado Oil (Refined) | ~270°C | Monounsaturated (oleic) | Excellent — high stability, neutral flavour; great for tempura, chips, fries. |

| Ghee (Clarified Butter) | ~250°C | Saturated / some MUFA | Excellent — adds flavour, very stable; ideal for roast chips or shallow frying protein. |

| Peanut Oil (Refined) | ~230°C | Monounsaturated | Very good — classic for deep frying; mild nuttiness suits many dishes. |

| Canola Oil (Refined) | ~204°C | Monounsaturated | Good — widely available; choose refined and check for high-oleic variants where possible. |

| Extra Virgin Olive Oil | ~190–207°C | Monounsaturated (plus antioxidants) | Good for shallow frying; EVOO adds flavour but is better used for low-medium heat or finishing. |

| Coconut Oil (Refined) | ~204°C | Saturated | Good — stable and flavourful, but watch total saturated fat in diet planning. |

| Sunflower Oil (High-Oleic) | ~225°C | Monounsaturated (if high-oleic) | Good — high-oleic varieties perform much better than standard sunflower oil. Check the label. |

| Flaxseed Oil | ~107°C | Polyunsaturated (omega-3) | Poor — do NOT heat; use cold only (dressings, smoothies). |

| Standard Sunflower / Safflower / Grapeseed | ~107–160°C | Polyunsaturated | Poor — unless labelled high-oleic, avoid for deep frying. |

Key research supports the superior frying stability of high-oleic oils and shows that repeated frying with PUFA-rich oils increases polar compounds and aldehydes. [2][6][11]

Now let’s apply this to the real kitchen.

The Top Tier: Your Go-To Frying Oils

Avocado Oil (Refined) — What: neutral flavour, very high smoke point. Why: high oleic content gives great oxidative stability. How to apply: use for tempura batters, fries and any high-temp frying. Race-week: use for a small serving of chips day-before long run rather than PUFA oil.

Ghee — What: clarified butter with milk solids removed. Why: high saturated fat content and removal of solids increases smoke point and reduces burning. How to apply: shallow fry fish or roast potatoes in ghee for robust flavour and stability; great for winter training days and long-recovery meals.

Light/Refined Olive Oil — What: refined, neutral olive oil (not extra virgin). Why: retains MUFA benefits with a higher smoke point and neutral taste. How to apply: versatile for pan-frying and shallow frying across training weeks; suitable for pre-race carbohydrates prepared the day before. (Australian olive oil consumption trends are rising; pantry-friendly.) [4]

Solid, Reliable Choices for Your Kitchen

Peanut Oil — Classic for reason: high smoke point and pleasant flavour, suited to Asian-style stir-fries or fish and chips.

Tallow & Lard — Traditional animal fats are stable thanks to saturates and are perfect for very crisp chips. For athletes wanting highest crisp and minimal oxidation, rendered fats are a practical choice (but account for total dietary saturated fat across the week).

Here’s the thing: the best oil often depends on the dish. Tempura and delicate batters: neutral avocado oil. Hearty roast potatoes: ghee or tallow.

Oils to Absolutely Avoid for Deep Frying. Period.

- Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) — use it for finishing and dressings; it’s great for low-medium heat shallow frying but not ideal for repeated deep-frying.

- Flaxseed Oil — extremely low smoke point; beneficial when cold only.

- Standard Sunflower / Safflower / Grapeseed / Many ‘Vegetable Oils’ — unless explicitly labelled high-oleic, these oils are PUFA-heavy and break down quickly when heated. Avoid for regular deep-frying. [2][7]

How to Deep Fry Smarter at Home

We keep getting the same practical questions, so here’s the performance-first kitchen checklist for athletes.

Nail the Temperature. I Can’t Stress This Enough.

What to do: set a target temp (175–190°C) and keep a thermometer in the oil. For chips and fries aim for 175–180°C; for thin battered items you can edge toward 185–190°C for short periods.

Why it works: If oil is too cool, foods absorb oil; if too hot, you accelerate oxidation and risk charred exteriors. Stable temp = less oil uptake and fewer oxidation products.

How to apply: during Sunday meal prep, heat oil slowly, aim for proper batch size (see below), and allow 2–3 minutes between batches for recovery. If you’re doing a post-long-run fry session, do the frying before the session or well after recovery to avoid inflammatory overlap.

Don’t Crowd the Pan

What to do: fry in small batches so oil temperature doesn’t plunge. Use a deep-fryer or wide pot; keep pieces uniform.

Why it works: large additions reduce oil temp and increase time food spends absorbing oil — that’s a texture and metabolic problem.

How to apply: for family-sized chips, do 3–4 small batches and keep finished fries warm in a low oven (120°C) rather than refrying them all at once.

Filter and Reuse Your Oil Wisely

High-quality, stable oils can be reused a few times if handled correctly. The commercial sector uses filtration, topping-up, and systematic replacement to keep quality high; you can take the same approach at home.

What to do: once cooled, strain oil through a fine sieve or coffee filter to remove crumbs. Store in a labelled container, in a cool, dark cupboard.

Why it works: food particles accelerate oxidation during storage and subsequent heating. Removing these reduces secondary oxidation and extends oil life.

How to apply: expect 2–4 uses for stable oils (avocado, ghee, high-oleic sunflower) depending on food type (breaded items shorten life). Discard oil if it smells rancid, darkens or foams on heat. [1][11]

And because you asked: if you use frying for race-week comfort food, do it earlier in the week and keep portions conservative. Use UCAN Energy Gel 15–30 minutes before short high-intensity sessions that follow a higher-fat meal to stabilise glucose availability, and use UCAN Energy + Protein after the session to support glycogen resynthesis and muscle repair. 👉 Shop UCAN Energy Gels [12]

Frying Oil Myths That Drive Me Crazy

There’s a lot of noise. Let’s separate what matters to athletes from the marketing slogans.

Myth 1: Saturated Fat Is the Enemy in a Fryer

Reality: under high heat, saturated fats are chemically stable and less likely to form reactive oxidation products. That doesn’t mean load your diet on saturated fat, but using ghee or tallow occasionally for frying is an evidence-based choice for stability. Keep weekly totals sensible (context matters for cardiovascular risk profiles).

Myth 2: ‘Vegetable Oil’ Is a Healthy Choice

Reality: “vegetable oil” is a label that hides a blend of seed oils (soybean, corn, canola). These are often refined and PUFA-heavy — not ideal for repeated high-heat frying. If a bottle says only “vegetable oil”, leave it for salad dressings or back-of-cupboard non-heat uses.

Bottom line: read labels — if the bottle isn’t explicit about the type of oil and it’s cheap, assume it’s a PUFA blend and avoid for deep frying.

Myth 3: All Seed Oils Are Bad

Reality: nuance matters. Some seed oils are now bred to be high-oleic — meaning most of the fat is oleic acid (monounsaturated) rather than linoleic (PUFA). High-oleic sunflower and rapeseed can perform well for frying and have much better oxidative stability than their standard counterparts. Always check the label and prefer high-oleic versions where possible. [2][7][12]

Frying Oil FAQs: Your Questions Answered

Can I Reuse Frying Oil?

Yes — but only if it’s a stable oil (avocado, ghee, high-oleic sunflower, refined peanut), filtered and stored correctly. Expect 2–4 uses depending on the food fried (breading reduces usable cycles). Discard if dark, foamy or rancid. [1][11]

What Is the Best Budget-Friendly Oil for Frying in Australia?

If avocado oil is too pricey, light/refined olive oil (not extra virgin) and refined peanut oil are good, affordable choices available at Coles/Woolies. Check for high-oleic labelling on sunflower/rapeseed options. [4][16]

How Can I Tell If My Oil Has Gone Bad?

Your senses are the first line of defence: rancid or off smell, darkening colour, increased foaming on heat, and sticky residue are all discard indicators. From a performance point of view: don’t risk it — fried foods that taste “off” are not worth the inflammation trade-off during a heavy training block.

References

[1] Grootveld M, et al. Experimental revelations focused on toxic aldehydic lipid oxidation products and their dietary significance. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022. (Review on lipid oxidation products formed during frying). PMC article.

[2] Romano R, et al. Oxidative stability of high-oleic sunflower oil during deep frying. Food Chem. 2021. (Study on high-oleic sunflower behaviour in frying). PMC article.

[3] Abrante-Pascual S, et al. Vegetable oils and their use for frying: a review. 2024. (Review on frying and oil quality; oxidative stability emphasis). PMC article.

[4] USDA / Australian Oilseeds and Products Annual reports. (Market data on oil consumption in Australia — useful context for availability and trends).

[5] Zhou Z, et al. Comparative analysis of frying performance of various oils. 2024. (Comparative review of lipid oxidation and frying outcomes). PMC article.

[6] Sun M, et al. Effects of different frying oils composed of various fatty acids. 2023. (Chemical alterations during deep-fat frying and implications). PMC article.

[7] Aladedunye F, et al. Frying stability of high-oleic sunflower oils as affected by storage and frying conditions. Food Chem. 2013.

[8] For general smoke point reference ranges and practical kitchen values see the Cooking Oils smoke point data compiled in technical reviews and food science resources.

Practical UCAN Notes & Product Mentions (applied to training)

Use UCAN products to complement smart fuel choices around fried meals and heavy training days:

- Pre-intervals (e.g., 10×400m or 8×800m): take a UCAN Energy Gel 15–30 min prior for stable glucose release on sessions started within 1–2 hours of a higher-fat meal. 👉 Shop UCAN Energy Gels

- Post-session recovery: UCAN Energy + Protein 20–30g within 1 hour to optimise carb:protein balance for glycogen and repair.

These mentions are purpose-driven — use product solutions where they solve a training problem (steady power for hard intervals, recovery after long sessions), not as a substitute for a balanced diet.

Author & E-E-A-T

Author: Generation UCAN

Last updated: 15 October 2025

Call to action: For race-week fuel planning and product recommendations tailored to your event (Sydney, Melbourne, Gold Coast Marathon, Ironman Cairns), check our race-specific guides and shop: Performance recipes • UCAN Energy Gel.

Note: this article focuses on oxidative stability and practical athlete application. For clinical questions about cardiovascular risk and saturated fat intake, consult your sports dietitian or GP.

Comments are closed