Quick takeaways: 1) Use a three-phase warm-up: movement → mobility → activation. 2) Adjust duration to session intensity and weather. 3) Fuel 30–45 minutes before heavy sessions for steady energy.

Contents

Why Your 5-Minute Jog Isn’t Enough

Most runners treat warming up as a checkbox: 5 minutes of shuffling and they call it done. That’s why your first kilometre often feels heavy and awkward. A meaningful warm-up has three clear goals:

- Boost blood flow: Gradually raise heart rate and muscle temperature so metabolic reactions and contractile speed increase.

- Prime the nervous system: Improve motor-unit recruitment and intermuscular timing — you’ll run with better coordination and faster cadence responses.

- Activate key muscles: Specifically target glutes, hip extensors and core so they aren’t “sleepy” for your first hard efforts.

What that looks like in practice: rather than “run until warm”, do 10–20 minutes of structured work. For example, before a threshold session: 7–10 minutes easy jog, 6 minutes dynamic mobility, 4–6 minutes of activation and 3–4 short strides. That sequence turns a sluggish opening kilometre into a powerful first rep and preserves performance across the set.

Why it works (brief physiology): warming raises muscle temperature which improves cross-bridge cycling speed and reduces muscle stiffness; potentiation from activation drills increases force output for short, high-intensity efforts and reduces early fatigue during repeated intervals. These effects are well described in performance literature and meta-analyses of warm-up protocols.[1]

The Three-Phase Warm-Up Protocol That Actually Works

Keep the structure — three phases that flow into each other. Below are practical cues, why they work and how to apply them to Australian training and race-day situations.

Phase 1: General Movement and Blood Flow (The Ignition)

What to do (5–7 minutes): easy jog or skip; maintain conversational breathing. Example: 5 minutes at ~60–65% HRmax (or 1.5–2 RPE). If it’s very cold, extend to 8–10 minutes.

Why it works: raises tissue temperature, increases glycolytic and oxidative enzyme activity, and ramps cardiac output slowly to avoid early lactate accumulation when you hit higher intensities.

How to apply: on Melbourne winter mornings, extend Phase 1 by 3–5 minutes. Before a Gold Coast summer tempo, keep Phase 1 light and brief to avoid overheating — use time-of-day training to mimic race timing.

Phase 2: Dynamic Mobility (Opening the Joints)

What to do (5–8 minutes): controlled dynamic drills that move joints through their running ranges: leg swings forward & sideways (10–12 each leg), walking lunges with thoracic twist (8–10 each leg), hip circles (10 each direction), ankle rocks and high-knee walks for 20–25m.

Why it works: dynamic mobility improves range of motion in sport-specific planes and prepares tendons and fascia to accept elastic loading at speed without compromising strength — unlike static holds which can temporarily reduce force output.[2]

How to apply: perform these on grass or soft pavement before intervals. If you’re prepping for Martin Place or the hilly Sydney Harbour course, emphasize hip flexor and thoracic rotation work so your stride stays efficient on climbs.

Coach’s cue: Move under control. A purposeful 90° hip lift or a smooth forward leg swing is more valuable than a ballistic fling. Quality over style points.

Phase 3: Activation and Potentiation (Flipping the Switch)

What to do (3–6 minutes): muscle activation and nervous-system priming: 12–15 glute bridges (pause and squeeze), A-skips and B-skips for 20m each, 2–4 accelerations/strides over 80–100m building to ~80% pace.

Why it works: activation lifts motor unit recruitment thresholds and potentiates fast-twitch responsiveness — you’ll produce more force on ground contact and tolerate higher cadence without losing economy.

How to apply: before a track session (e.g., 8×400m @ 5k pace), follow activation with 3–4 x 100m strides at session intensity to ensure your neuromuscular system is synced. For triathletes off the bike at Ironman Cairns, prioritise glute activation and single-leg drills to redevelop running mechanics after cycling.

Optionally combine phases if time is tight (example: 7 min movement + 5 min combined mobility/activation) — but do not skip activation before high-intensity efforts.

Sample Warm-Up Routines for Different Runs

| Phase | Easy Run Warm-Up (10–12 mins) | Interval Session Warm-Up (15–20 mins) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. General Movement | 5–7 mins easy jog (conversational) | 7–10 mins easy jog including light skipping |

| 2. Dynamic Mobility | Leg swings (10 each), walking lunges (8/leg) | Leg swings, hip circles, walking lunges with twist |

| 3. Activation | 2 x 80m strides at a floaty pace | Glute bridges (15), A-skips (20m), 4 x 100m strides |

How to Adjust Your Warm-Up for Aussie Weather

Australia’s climate extremes demand simple adjustments. The sequence (movement → mobility → activation) stays the same; the proportions change.

Cold Winter Mornings

What to do: add 3–5 minutes to Phase 1 and stay moving between mobility and activation drills. Use extra layers until you’re at the start line and remove them last-minute.

Why: cold muscles have higher stiffness and reduced power output. A longer ignition phase increases intramuscular temperature and reduces strain on connective tissue during higher loads.

How to apply: Before a Melbourne half or Canberra tempo, wear a tracksuit to the start of your jog and peel layers during Phase 2. Time your final strides so they finish 5–10 minutes before race start — then keep light jogs on the spot if you’re waiting in a corral.

Hot and Humid Summers

What to do: keep Phase 1 brief (4–6 minutes), monitor perceived effort closely, and prioritise hydration and heat-acclimatisation strategies in the days before the event.

Why: excessive early exertion increases core temperature and sweat rates; starting too hot will reduce your capacity for sustained efforts on humid Gold Coast mornings.

How to apply: schedule hard sessions for cooler parts of the day, sip an electrolyte drink before you warm up and use light exposure training (short, repeated sessions) across a 2-week block to adapt if racing in heat.

This article includes an embedded video walkthrough of the three-phase warm-up — keep it handy for visual cues:

How to Fuel Your Warm-up Properly

Fueling for the warm-up is often ignored. If your first interval feels flat, poor pre-warm-up nutrition is a likely cause.

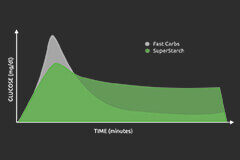

The Problem with Sugary Gels

Taking a high-sugar gel 5–10 minutes before your warm-up creates a rapid glucose spike and reactive drop in blood sugar — not ideal right at the start of high-intensity work. You may also provoke gut distress if you start hard while digestion is still ramping up.

A Smarter Fuelling Strategy

What to do: take a low-insulin, steady-release carbohydrate source 30–45 minutes before hard sessions (example: UCAN Energy Gel), or choose a small, low-fibre snack 45–60 minutes beforehand for longer sessions. For sessions under 60 minutes, a single UCAN Energy Gel 30–45 minutes pre-start provides steady power without the spike-and-crash.

Why it works: slow-release carbs maintain blood glucose steadily throughout your warm-up and early reps, reducing perceived effort and stabilising pacing during the first interval or race kilometre.

How to apply: for an interval block (e.g., 6×1km @ 10k pace) take a UCAN Energy Gel 30–45 minutes prior. For long runs and brick sessions, combine a small pre-run meal 90 minutes out with a UCAN gel 30 minutes before you start moving.

For hydration and electrolytes in hot conditions, pair your pre-warm-up strategy with a concentrated electrolyte drink — see our Ultimate Guide to Electrolyte Drinks for practical recipes and timing.

Common Warm-Up Blunders I See at Every Race

On race day I still see the same mistakes. Fix these and you free up instant performance.

The Static Stretching Trap

The Mistake: holding long static stretches immediately pre-race (30+ seconds).

The Fix: move to dynamic mobility and do static lengthening post-run. Static holds can reduce force and power in the first 10–20 minutes of exercise.[2]

Warming Up Too Early

The Mistake: finishing your warm-up 20+ minutes before the start and then standing in the corral.

The Fix: time your warm-up to finish within 5–10 minutes of the gun. If you’re stuck waiting, stay warm with light bounces, short jogs in place or repeat 2–3 short accelerations to keep the nervous system primed.

Your Pre-Run Warm-Up Questions Answered

How long should my warm-up actually be?

Short answer: it depends. Easy runs: 10–12 minutes. Track or tempo sessions: 15–20 minutes. Races: follow your interval warm-up but finish 5–10 minutes before the start. Use HR and perceived effort as practical guides — aim to be at ~60–65% HRmax during Phase 1 and increase intensity gradually.

Do I really need to warm up before an easy recovery run?

Yes. Even 5–10 minutes of activation reduces muscle soreness and improves blood flow, accelerating recovery. Think of it as prep for repair — a short warm-up signals the body to shuttle nutrients and clear metabolites more effectively.

Should I do my normal warm-up before a race?

Yes — but time it. Keep the same three phases and scale intensity to event distance. For a marathon (e.g., Gold Coast or Melbourne), shorten strides and prioritise smooth neuromuscular priming. For shorter, faster events, spend a bit more time in activation and do 2–4 race-pace strides.

References

[1] Fradkin AJ, Zazryn TR, Smoliga JM. Effects of warming-up on physical performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine. 2010;40(2):135–145.

[2] Behm DG, Chaouachi A. A review of the acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2011;111(11):2633–2651.

Ready to fuel your runs the smart way?

If you’re serious about squeezing every last bit of performance from your training and race day, pair this warm-up with steady-release carbs that avoid spikes and crashes. For sessions requiring steady power early on, a UCAN Energy Gel 30–45 minutes pre-start is a practical, race-proven option.

Comments are closed